—-

To stay in the loop with the latest features, news and interviews from the creative community around licensing, sign up to our weekly newsletter here

Yaron Lifschitz, CEO and Artistic Director at Circa, tells us about the creative process behind bringing the iconic Aardman brand to life in the form of contemporary circus.

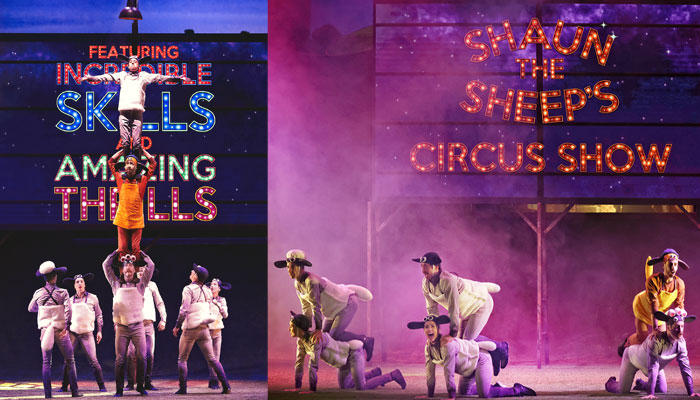

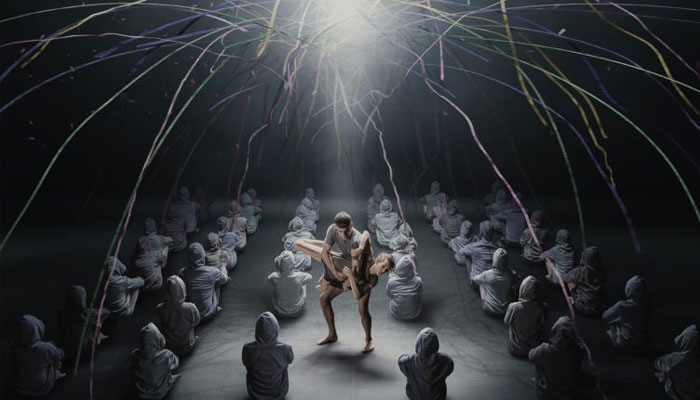

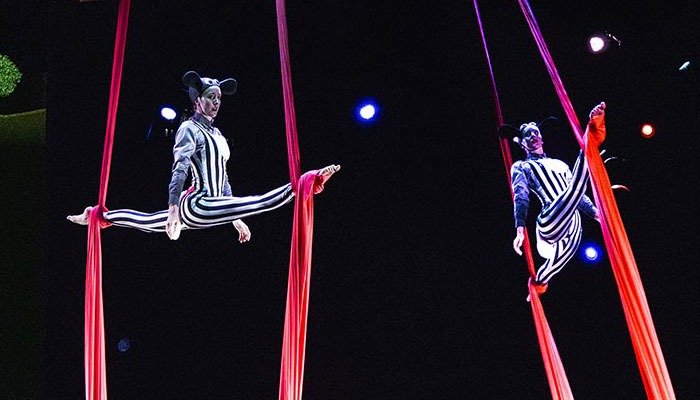

Circa Contemporary Circus, one of the world’s leading performance companies, has been hailed as ‘a revolution in the spectacle of circus’, known for shows boasting extreme physicality that blur the lines between movement, dance, theatre and circus.

As such, it perhaps came as something of a surprise when it was announced that Circa’s next show would be a collaboration with renowned animation studio Aardman in the form of Shaun the Sheep’s Circus Show.

As the show prepares to debut at QPAC’s Lyric Theatre in Queensland, Australia, we caught up with Yaron Lifschitz, CEO and Artistic Director at Circa, to find out about why giving Shaun the Sheep the Circa treatment has been one of the toughest creative challenges of his career.

Hi Yaron, thanks so much for taking time out for this. First off, I know very little about the circus space, so how did you get involved in this industry? Do most people come to it from other areas of the arts?

Well, it’s not a big field, it’s a mid-size field. Some people start directly in circus and train as circus artists; they perform for years and then go on to create shows. Others create shows first and are circus natives. I trained as a theatre director and went to the National Academy here in Australia.

“We’re going nuts! There’s jokes, there’s sheep, there’s wool; look, it’s a new world for me!”

I started to direct shows – plays mainly – and discovered I didn’t like plays very much because they were full of people talking about stuff that didn’t happen. I remember there’s a line in The Simpsons where Homer is at a zoo and he goes up to some tigers laying in a cage and says “I’ve seen PLAYS that were more exciting than this… honest to God, PLAYS!” That’s how I felt back then and mostly still do. I think theatre got enslaved by literature; it’s been taught to be about a bunch of themes and ideas. I knew it wasn’t my calling.

So I worked in events, in opera and for five years I ran an artist-in-residence programme at a The Australian Museum in Sydney, the oldest cultural institution in Australia. I felt like the world was a much more interesting place than the staged version; people talking about their gay divorced, middle-aged alcoholic son, or whatever the play was.

So a desire to work in something more creatively challenging took you into the circus?

Well, I always knew that the thing that would interest me the most would be to dive deep into something that had a narrow set of languages. There were three companies in Australia at the time that I felt I could take in an interesting direction; one was a contemporary opera, one was a puppet company and one was a circus company.

The circus company came up first, I got the job and then I spent five or six years getting the worst reviews you could possibly imagine. The whole thing was a complete catastrophe, but we would always see these little embers of ideas and from those we created a way of working that became a very strong house style.

For anyone that hasn’t had the pleasure of seeing a Circa show, how would you sum that style up?

It’s very stripped back, very physical and very much about how the body can become the site of emotion and expression. That approach has served us really well from when we started touring internationally in 2005/2006 to 2011/2012, and then we began to evolve and stretch our ambitions, to do shows in cemeteries in London and we’ve made films and operas.

We have a curiosity and a restlessness. To use a drinking metaphor, it’s like a fine spirit that’s very strong, so you don’t always want to drink it raw. Sometimes you want to mix it and make a cocktail with it. Now that we’re very confident about what the spirit is and we’ve distilled it to a point of clarity, we can pour it liberally into lots of different vessels.

Circa has been hailed for exhilarating, innovative and sometimes quite unexpected shows; is that typical of the sorts of projects you seek out?

I’m very curious, I’m restless and I don’t like to believe things just because they’re so; I have an interest in what lives under the hood. Yates said: ‘Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrels with ourselves we make poetry’. I don’t know anybody that pushes deep into the night because they like the idea of innovation. I think we do it because it comes from a deep, inexplicable and often wordless place within ourselves. We trying to understand it, live with it and stop it eating at us.

I make a lot of shows; some years perhaps eight or ten new shows. Most circus directors will make one or two. I feel a bit like the beaver who has to keep gnawing on wood because otherwise their teeth grow too long and they die because they can’t eat food. I’m a bit like that with shows. I don’t always know why I make them but I feel a compulsion to push my shabby stuff out into the world.

“In the show, one of the sheep does a burlesque act where she shears herself down to her bra and pants. I was convinced that Aardman was going to have a problem with it, but they were like ‘great idea! That sounds fabulous!’”

Delving into that compulsion a little, what are those first steps like when you’re putting together a Circa show? Does it start with a story or can a stunt sometimes be the launchpad?

It’s a great question and I don’t know that there is a method. The method is what you do to get you to the starting gun. Sometimes you wake up with a great idea. Sometimes you get to the end of a process three years down the track of touring a show and think ‘why did I even make that show? It was a dumb idea.’ Some of the best shows we’ve made have never been touring successes and some shows that have had long lives and grown into very beautiful things started out with the worst skeleton of a half-baked idea.

I’m very lucky because I work with very talented people who can fill a stage with excitement. My process is very simple. If you think about an oyster, it gets a grain of sand in it and that irritates the oyster into producing a pearl. My job is to be the grain of sand. At some point, I have to disrupt, whether that’s the acrobatic pathway, the theme or the performance itself. My job is to be the irritant, but not just for the sake of irritating. You can irritate an oyster and not end up with a pearl in the same way you can irritate a process and just be bloody annoying. And the two aren’t mutually exclusive; I can create beauty and be bloody annoying. That’s even quite common! But yes, it’s about having that ability to home in and see that by disrupting an element, it could create beauty.

That’s fascinating. Can you give me an exciting example of the sort of irritation or disruption you might use when creating a show?

It can be very simple. Lots of acrobatics comes out of stuff like, ‘climb up, but climb up without using your hands’. Suddenly all these pathways and thinking is activated. I’m fascinated by the fact that we’re neurobiological machines that are extraordinarily complex but our bodies are these kinds of living sculptures. People stand and gawp at Michelangelo’s David like it’s a masterpiece when it’s a really good copy of something nature created and that we’re all blessed with. Avoid the queues and look in a mirror!

Another thing we’re all blessed with is the work of Aardman, and you’ve teamed up with the studio to create Shaun the Sheep’s Circus Show, a brand new Circa show blending animation, live acrobatics and plenty of surprises we won’t ruin here! It’s not the sort of collaboration many would have guessed, so talk us through your approach to giving Shaun the Sheep the circus treatment? What’s it like creating something based on a brand?

We’re going nuts! There’s jokes, there’s sheep, there’s wool; look, it’s a new world for me!

I often think I have an immediate boss which is the audience, and my success is based on my ability to authentically communicate with them, whether they like the show or not. Then there’s the overseers who I’m deeply responsible to, which is the 10,000 year old tradition of live performance; the ritual, the ecstasy, the reason why you perform live, the reason people still go to church and to rock concerts – that electric moment we all share together. Then there’s the mass of style guides, brand bibles and perceived practices that you get when you’re dealing with clay sheep!

Ha! And how has it been working with Aardman? You’re both very different companies but there seems to be a creativity and a playfulness that you share.

These beautiful, kooky, surreal Bristolians are super-talented and I love what they do. They also have a great admiration for what we do, so it’s been a great meeting.

Of course, we see the world in fundamentally different ways. Their world is two-dimensional; almost everything they do is translated from three dimensions into two dimensions. We’re the exact opposite; we take things and add dimensionality. We’re quite often talking different languages and we have to figure out how to get those languages to match up.

So with those polarising viewpoints, what has been the key to making the collaboration work?

As with most things in life, it begins and ends with the relationship, and relationships are based on communication, trust and the ability to course-correct. We’ll say things and they’ll think we don’t know anything, and they’ll say things and we’ll think they won’t work in our world. We’re very good at what we do and they’re very good at what they do. We had to find a communal space.

What’s interesting is that I’ll go to a meeting with Aardman and I’ll bring 50 ideas. I’ll think ‘these five will be the problem’, but they’re never the problem! The problems are things that I thought would be so easy to accept because, in my world, they’re so mundane. It continually perplexes me!

Having immersed yourself in the world of Shaun the Sheep, how did you decide what elements would translate well into a live circus show? Were there parts of that world you knew straight away would slot into a Circa show?

It’s been one of the hardest creative adventures of my life – when I finally cracked the spine of the story, I was so relived. It’s difficult, but it makes sense because Shaun the Sheep is non-verbal, highly physical and has a great sense of comedy and human warmth. It’s well-loved so we’re starting from a position of people liking the idea and engaging with it. There’s also a great sense of cheekiness and play.

The circus is a big affront to entropy. If you and I sit on the sofa, we can eat a pack of crisps and watch the telly. We just get marginally wider and a bit less thermodynamically effective. In circus, you’re doing the opposite. You’re constantly building things and putting them in motion; that requires energy and motion. In Shaun the Sheep, there’s always this spark of cheeky energy that starts an episode or causes something to happen. That really connected with us. Circus is all about doing things that require effort, and that often comes from a sense of playfulness, fun and a desire for admiration. Those are all qualities that you see in Shaun the Sheep.

“Fear is a very good driver, and so is doubt. I like to start every project with ‘let’s not fuck this up’ and finish it with ‘we fooled them again!’”

Is this kind of collaboration rare? Or has the circus got a rich history of working with brands?

Well, Harry Potter is on stage and Shrek has a musical, so there is a hunger for live performance, but our Shaun the Sheep show is quite different. Our work is usually hard-edged, quite uncompromising and pretty savage. It features very strong women who pick men up and it’s very contemporary. What I like about this interpretation is that it’s not us coming along and acting out Shaun the Sheep. Instead, we’re smashing into this world and watching the lambs fly! It’s weird, joyful and messed up all at the same time.

You mentioned there that your work is usually quite uncompromising. Was there any fear that by doing Shaun the Sheep you’d be asked to smooth down your edges and water down what Circa is known for?

This is what keeps amusing and amazing me. The edges aren’t the problem. In the show, one of the sheep does a burlesque act where she shears herself down to her bra and pants. I was convinced that Aardman was going to have a problem with it, but they were like ‘great idea! That sounds fabulous!’ Then I wanted a shot of a character outside in our reality, but they said it was too complicated because you can’t mix the worlds. The brand thinking is very different to ours.

I’m glad the burlesque got the green light though because that sounds brilliant; and it sounds like the compromises are actually pretty straightforward?

Well, one is the size of the sheep relative to people; it’s an obsessive thing at Aardman! I still don’t know what size the sheep are supposed to be and I probably never will. It’s a bit like theatre with lots of unwritten rules, but it’s a democracy; you just have to find a space where you agree on 90%. Everyone then avoids the 10% and you lead a good life. That’s been forgotten in our political system today and I imagine it’s been forgotten in a lot of brand-based collaborations.

And I’d say a lot of brand collaborations in the theatre space follow pretty closely to the source material, telling the same story with actors dressed as the characters. It must be great to be able to grapple with Shaun the Sheep in a way that remains true to what you guys do?

Yes, and Shaun the Sheep has had some good stage adaptations, but none have come close to being as popular as the movies or the TV show. The reason for that is people are trying to do Shaun the Sheep as the TV show on stage and there’s a limitation to that. We’re creating a fantasia. It’s a bizarre, lethally post-modern riff on Shaun the Sheep, and it’s bonkers.

The TV show is bonkers, and in the episodes, they go to amazing places. I love that about it and we knew we wanted to push the boundaries. Not only was Aardman up for it, they encouraged us and that was a great place to start from.

I really want to see this now Yaron; I hope it comes to the UK.

Oh, it’ll come to the UK. You guys are clearly a key audience for us.

Brill, count me in. Before I let you go, I wanted to ask how you personally fuel your own creativity?

I’m not particularly a creative person. I like solving problems and I like triangulating things. To be honest, I look around and I see 60 staff – my family – who need their mortgage paid, and I think ‘I better not fuck this up’. From there, whatever it takes not to fuck it up is what I need to do. I wish I had a more interesting answer!

I’d argue problem solving is its own form of creativity, but you’re right, not wrecking something is pretty good fuel!

Fear is a very good driver, and so is doubt. I like to start every project with ‘let’s not fuck this up’ and finish it with ‘we fooled them again!’ We’re not going to make masterpieces with every show we make. We have to be respectful of the difficulty of the thing we’re doing. We have to have enough love for its force and its nobility to know that we can’t make it all amazing; that’s never going to happen. It’s not an excuse, it’s a drive to do better. As Beckett said: ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ That’s the experience. If you don’t finish a show with a burning desire about what’s coming next, you’re either very good or, more than likely, not very good.

Well, I’m convinced you won’t have messed this up because the way you’ve spoken about Shaun the Sheep’s Circus Show, it sounds like a winner. Good luck with it, I can’t wait to check it out, and a huge thanks again Yaron for taking the time to chat today.

Thanks mate, much appreciated.

Yaron main image credit: Margot Taylor

Enter your details to receive Brands Untapped updates & news.