—-

To stay in the loop with the latest features, news and interviews from the creative community around licensing, sign up to our weekly newsletter here

Sounds impossible! Mark Ayres explores the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s rise, fall… And rise again!

Thanks for joining me, Mark. I’m thrilled to be speaking with you about Spitfire Audio and the licensing of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s archive. For the uninitiated, what was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop?

From 1958, The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was the BBC’s electronic music department. But it came about by accident – or perhaps by persistent design – in a way with which its original enablers weren’t entirely happy… Basically, in the late fifties, Desmond Briscoe and Daphne Oram were two BBC studio managers. They were working at Broadcasting House in London, mainly on material for what was known as The Third Programme…

And what was that?

Today, we’d call it Radio 3! Back then, it was slightly different – it was the highbrow art channel. They did the classical music and plays considered to be of artistic merit! But Desmond and Daphne were very enthusiastic about techniques for pushing the art of sound. After the Second World War, they saw that the European studios and individuals were beginning to experiment in electronic music… Which is to say music made without traditional musicians and composition techniques, but mainly using the new instrument of the tape recorder.

Because – for context – the tape recorder was, at that time, comparatively new technology?

Yes. And in Paris, for example, Pierre Henri and Pierre Chef had set up a electronic music studio with France’s national broadcaster. A similar thing happened in Cologne where – later – Carl Stockhausen would work creating electronic music. But those studios were set up to explore electronic music specifically as an art form. They had very different mandates… The Paris studio was involved with what we call musique concrète – ‘concrete music’… Music made up of ‘found sounds’; sounds we hear in everyday life.

So if I were to record birdsong, say, that would be a found sound?

Exactly. You might use tape as a medium to manipulate that into something which has a different musical structure, but yes… You can deconstruct and reconstruct the sound of everyday things in musical ways: a speeding car, a breaking coffee cup, the pop of a cork from a wine bottle…

All of which I’ve heard this morning as it happens… So that’s Paris; concrete music. But in Germany?

In Germany, they were more interested in creating music made out of pure electronic sources: what we’d now call a synthesizer… Desmond and Daphne saw both of these things happening and thought it would be great if the BBC set up a similar studio. They imagined they could invite in the great and the good of British composers who were working in this field and get them to make art music for the BBC. Of course, the BBC were having none of that! Ha!

Ha! Well, we’re laughing because I think it’s fair to say that the BBC was a bit set in its ways back then.

Yes. Back then, the BBC high ups were very traditional; they felt electronic music was something newfangled and unnecessary, I think. As the UK’s national broadcaster, their role was to inform, educate and entertain. I don’t think they saw the value in this new form of music. Undeterred, Desmond and Daphne started experimenting overnight…

And when you say overnight, I know you’re being literal!

Right, because the radio stoped broadcasting at about half eleven at night. They played the national anthem; that sent everyone to bed and the staff at Broadcasting House went home. But Desmond and Daphne would stay on: they’d nick the gear from all the other studios, start experimenting with electronic music, then try to get everything back where it lived by six o’clock the next morning when the news started.

Ha! That’s amazing! And did any of the work they were doing like that end up being broadcast?

Well, eventually they did a few plays: Private Dreams, Public Nightmares was one… Under the Loofah Tree was another. Enough bits and pieces to make the BBC start to think these new sound effects would be quite useful for more abstract sounds. As Desmond pointed out in a 1960’s interview, the BBC was getting away from kitchen-sink drama and into plays about the mind, philosophy and psychology. But if you wanted the sound of someone having a nervous breakdown, where would you go for that?!

Ha!

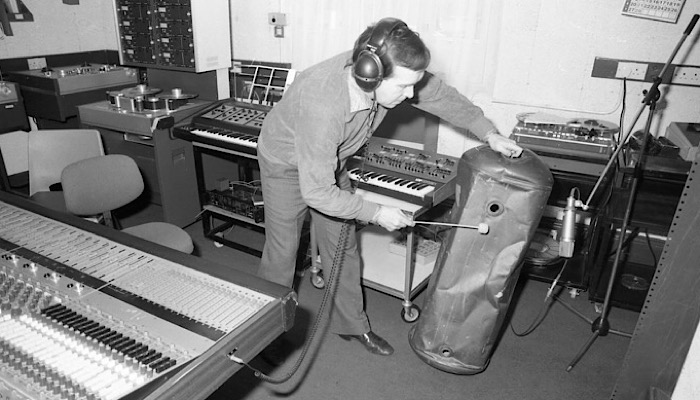

So this is where these new sounds came in. Eventually, the BBC gave Desmond and Daphne three months in rooms 12 and 13 at the Maida Vale building because nobody was using those. They were also given the key to the Redundant Stores department… In other words, all the bits of kit that nobody else was using – mainly because they were broken! And that’s how it started.

Extraordinary. When we come back to some of the groundbreaking work they did, Mark. I’ll focus on the original Doctor Who theme… That music is easily recognised – but maybe its genius isn’t! First, though, how did the licensed project with Spitfire Audio come about?

Well, Spitfire Audio is already known as a company that makes high-end sample libraries. They’d already created a sample library with BBC Studios and the BBC Symphony Orchestra. That’s now a must-have tool for musicians and sound designers! Then, few years ago, Spitfire, BBC Music and BBC Studios sat down to discuss creating a BBC Radiophonic Workshop archive with a sample library.

And out of interest, Mark, why did they come to you about that?

They came to me as the archivist of the material and the person who has, I suppose, promoted it more than anyone else over the past 30 years. We can talk about how that came to pass… But for Spitfire Audio and the BBC, I put together an initial ‘shopping list’ and they started building it. Then they came back and said, “This is great, but what else can we do that really says: ‘ta-daaaa!?”

Something really special…

Well, we all more or less came up with the same idea at the same time, because we knew the Maida Vale Studios was closing down. What if we spent a week in there? What if we did a whole load of new stuff using the original techniques, but with a digital mindset? And that’s what we did. So the licensed library is half real archive – going back to 1958, bottled for people to use. The other half is new stuff made in the same spirit! Our hope is that people will find great stuff on there that they can use… But also say, “I see how they did that. I’ll do something different!” So we’re hoping it will inspire as well.

Perfect! I want to understand how you came to the industry, Mark… For context, though, I’m keen to discuss the original Doctor Who theme. That’s because – despite it being over 60 years old – it still sounds, to me, totally unearthly. So in 1963, it must have sounded absolutely incredible…

Oh, yes! Absolutely! And I should probably say that, once set up, the department quickly got on the map with the film Quatermass and the Pit. A man called Tristam Cary did the score for that. This would be in 1953… So when the Radiophonic Workshop started doing dramas and things, they were quickly doing very well. People could see the value.

In fact, they were starting to do what Desmond and Daphne always wanted. That said, for years it was credited as special sound – not music. But sadly, Daphne left within the first three months because it wasn’t what she wanted to set up. They wanted a sound effects department and she specifically wanted to do art – but here they were doing television science fiction and radio comedy.

Yes, I can imagine doing the sound effects for Major Bloodnok’s stomach on The Goon Show didn’t feel like art– which is sad, really, because those sound effects were absolutely incredible!

Well, the especially sad thing is that if Daphne had stuck with it for a few years, I think it would’ve evolved in a different direction. But that’s a whole other story! With the Doctor Who theme, the feeling within the BBC was still that it should be written by a certified composer. Ron Grainer was given the task. He’d already worked with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop on an hour-long documentary about the death of the steam locomotive: Giants of Steam. Ron wrote the theme for it and wanted a rhythm track of the clankings, bangings and sounds of steam trains…

I love that you’re doing all the sounds as we talk, Mark! It’s a shame this is in print! Ha!

Ha! Well, Brian Hodgson at the Radiophonic Workshop created that rhythm track, then Ron’s music was recorded by a live band to put over the top. And I think that’s what Ron expected to happen with the Doctor Who theme. He wrote his music, gave it to one of the team – Delia Derbyshire – and imagined that he’d record a live band after she’d come up with a background. So his music was very simple: just a melody and a baseline, with indications of the occasional sound effect here and there.

But Delia Derbyshire had some other ideas…

She did! Delia joined the Workshop in 1962. She’d studied mathematics and music at university, so she was an ideal candidate – plus she’d also been a studio manager at Broadcasting House. Delia was hugely interested in what could be done manipulating sound. When she got this brief, she made the entire piece using tape.

And as people listen to the original Doctor Who theme – and they absolutely should stop reading this and play it now… As they do, they should keep in mind that there’s no musicians on it, there’s no musical instruments, there’s no theremin, no synthesizers…

No, no. Nothing like that!

So what, Mark, are people actually hearing?!

Ha! Well, the Doctor Who theme has a recognisable tune; it has a recognisable baseline. That baseline is a single recording of a guitar string stretched over a piece of wood. When plucked, it goes, ‘dung’.

One note? One string, plucked once?

Right. A recording of one note… Then the tape was looped. So now it goes dung, dung, dung, dung… And then, as that loop continuously goes round, the output is recorded on another tape recorder.

I’m with you so far!

But as you may know, that theme starts with dung da dung, dung da dung, dung da dung. That other note is an E at different dynamics… So what Delia did was vary the speed of the recording of the string which was looping around: dung, dung, dung, dung, dung… She recorded that as many E’s. She also recorded a ‘loud E’ – DUNG and some ‘quiet E’s’. DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung… And then the next note is a G.

Wow…

DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung… So all these tapes are going round, and she records them with different dynamics. Eventually, she’s got a tape of all the dungs, all the separate notes, which is about three hours long! Next, she goes through them, marking them up – in all their different dynamics – with a chinagraph pencil before cutting the tape up…

Wait! Writes on the tape, then physically cuts it up?

Yes. So now the tape that she’s spent hours and hours making is a collection of individual bits of tape, all hanging up: E loud, E quiet, B loud, B quiet… Hundreds of them. She cuts them all to the right length, and puts them together in the right order to make the baseline.

But this is incredible! All this work – and that’s just the baseline?!

Yes. And you know, I maintain that what the Workshop was doing was sampling, because they were using found sounds to make tonal music. So Delia was doing sampling using analog tape. Either way, she was manipulating sounds to create music… And what the Doctor Who theme did, and what the Radiophonic Workshop became very adept at doing, was making what is conventionally music in a very unconventional way.

Oh, my DAYS! I started off overjoyed with all this detail but actually, it’s quite stressful now that I picture it.

Ha! Well, I think the way they worked back then probably could be stressful. People did burn out. Although, to be fair, they did work in pairs. A man called Dick Hill would’ve done an awful lot of the tape cutting on that.

And let me just check something, Mark… Because the Doctor Who baseline doesn’t just go DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung, DUNG da dung… It has a sort of wheezing sound at the start of some of the notes…

Yes! And that sound was also recorded on a separate bit of tape. For that, Delia got a test-tone oscillator… They’re designed to test pieces of electronic equipment; they produce a very pure tone. If you turned a dial on it in different directions, it would go weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee…

How am I going to type this up?! Go on…

Ha! So what Delia did is take this test tone oscillator, turn it down, set it to a square wave, pitch it down and then record all those notes on another bit of tape. Then she cut all those up, put them back together where she wanted them… Then played that bit of tape to synchronise with the first one.

So the baseline notes are doing their thing, but another tape has the oscillating tone making it sound like they’re together?

You’ve got it! And the whole Doctor Who theme – and everything they did back then – is made using that technique. That’s also true of the thing that people often mistake for a theremin. That’s another test tone oscillator; it’s a sine tone.

All this work! It’s so mind-boggling. Just out of interest, how long was that theme?

The first version Delia did was two and a half minutes. In the early days of the show, though, they just faded it out after 20 seconds at the beginning.

20 seconds! Oh, it’s a crime.

Ha! Incidentally, there’s a very charming story, which you may have heard… The story goes that when Ron Grainer came in to listen to it six weeks later, he stood there dumbfounded. He eventually said, “Did I write that?” And Delia very modestly said, “Most of it, yes.” But he went away thinking, ‘Well, that’s done, isn’t it?!’

Ha! Amazing. You know, I’d just love to see the original sheet music! And for how long did they use that theme?

For 17 years. They tweaked it occasionally, but it was the same basic recording up until 1980 when Peter Howell did the next version. And that WAS entirely synthesized – because by then the equipment was available.

Amazing. Amazing! Thanks for making time to walk us through that, Mark. I know I went into the weeds with you there a little, but I really want people to understand how extraordinary this department was. I think it’s an extraordinary piece of music and often taken for granted.

Yes, I think you’re right. And to go back very slightly, I mentioned Tristram Cary earlier. Well, there were a couple of other things in this area which I think should be seen as watershed moments. The first was a radio play called The Japanese Fishermen. The BBC commissioned this with an electronic soundtrack – so that was their tentative step towards embracing it. It wasn’t done by anybody at the Radiophonic Workshop or Desmond or Daphne; it was by

Tristram Cary.

And not to interrupt, Mark, but what was the subject matter? Why would it have been desirable to go in the direction of electronic music?

Ah, yes! It was a play about fishermen going out of Hiroshima or Nagasaki to fish. While they’re a couple miles offshore the bomb drops.

Strewth…

That was in 1955, I think. Then the second thing that I think should be seen as a watershed moment was the Hollywood film Forbidden Planet. That had an electronic-music soundtrack, which – again – wasn’t allowed to be called electronic music… In the opening titles, it says ‘electronic tonalities by….’ And that was two French composers; a husband and wife team: Louis and Bebe Barron. They weren’t conventional composers; they’d been inspired by the German school, which was using music created entirely using electronic techniques. So every sound you hear in the film Forbidden Planet is created by Louis and Bebe Barron using an electric circuit specifically to make that sound.

And that was the second watershed moment, you feel?

Yes, the second watershed moment in popular culture, I think, as far as electronic music is concerned. Certainly in drama. And I think Doctor Who is probably the third, coming up in 1963.

Given all its extraordinary achievements thereafter then, Mark, why did the BBC Radiophonic Workshop come to an end?

Well, there were three very distinct periods in the Radiophonic Workshop’s history. There was tape, there was voltage control and there was digital synthesis. Those were the big techniques based on technologies of their time. By the 1990s, the Workshop had all these very nice electronic music studios. They were well kitted out by that time because Brian Hodgson had fought for a lot of budget, and also fought for companies like Yamaha to give them great deals on all the latest kit…

The problem was that, eventually, people like me could also buy this gear on the high street. Back when the Radiophonic Workshop started, nobody else could afford it but – by the end – you could save up a bit of money and buy a synthesizer on the high street. Then you could buy two! So suddenly people like me were able to compete directly with the Workshop.

Right. So it would’ve been a question of cost?

Absolutely. And I should clarify: I’ve never been on the staff of the BBC; I never joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. I was a massive fan of it, because if you grew up in the 60s and 70s in the UK, their work was all over everything! Doctor Who on the Saturday night, Blue Peter in the week, schools programs, any documentary you watched in the evening… And I was fascinated by it.

I saw all these names on television programs that I loved: Brian Hodgson, Malcolm Clarke, Dudley Simpson, Tristram Cary… I was in my teens and, as a fan, I contacted them! And Dick Hills very kindly showed me around the workshop when I was about 15 years old. I also, in the early 80s, wrote to Dudley Simpson. He very kindly invited me to come and watch some of his sessions. So these people became my friends as well as my mentors.

But you did freelance for the BBC, did you not?

Yes – eventually, I got to work on incidental music for Doctor Who when the producer, John Nathan-Turner, started using freelancers because the work was becoming too much of a millstone around the Workshop’s neck. So I came in to do my first big composing job in 1988. It has to be said, my journey is one that wouldn’t happen now. It was a lot of happy accidents and very kind people giving me a chance.

That makes sense. And I’m so sorry – I think I interrupted you! You were telling me how it came to an end…

Yes. So toward the end, the BBC also introduced a thing called ‘Producer Choice’ where every BBC department had to cost itself to save money. In effect, The Radiophonic Workshop costed itself out of business and shut down in 1996. When it closed, I got three phone calls in quick succession; one each from Brian Hodgson, Peter Howell and Paddy Kingsland. They said the Workshop was dead, unfortunately, and that all these tapes and bits of kit would be heading for the skip.

And they couldn’t stop that happening?

No, they couldn’t stop it because they no longer worked at the BBC; they couldn’t get into the building. So it needed someone who knew it and loved it to go in.

So in YOU went!

In I went! They also found a very supportive producer at Broadcasting House called Colin Duff who basically gave me the keys and said, “You can sort it out!” So I spent two years there putting labels on everything and putting them all back in the BBC archives so that we could do this kind of thing in the future. And then – in the early 2000s – we all got together and said, “We’re not dead yet – let’s form a band!”

So we formed a band called the Radiophonic Workshop… Not the BBC Radiophonic Workshop because we’re independent, but the BBC have supported us all the way. And as the Radiophonic Workshop, we’ve done films and albums and we’ve played festivals and so on. And now we’re here doing this stuff!

What an extraordinary story. And is this licensing arrangement bittersweet for you in any way, Mark? That seems like a somewhat delicate question…

Actually, a couple of people have asked me something similar: do we feel like we’re letting this stuff go – and I don’t, actually. In fact, we all feel like we’re passing it on. And that’s the right thing to do because this stuff is important… I think it’s important to preserve it, celebrate it and pass it on.

Preserve it, celebrate it and pass it on. Wonderful. What a great note to end on! Thank you so much for your time, Mark. I’ll include a link to the Spitfire website here but for me this has just been fantastically interesting. Thank you.

Enter your details to receive Brands Untapped updates & news.